NASA has new evidence that the most likely places to find life beyond Earth are Jupiter’s moon Europa or Saturn’s moon Enceladus. In terms of potential habitability, Enceladus particularly has almost all of the key ingredients for life as we know it, researchers said.

New observations of these active ocean worlds in our solar system have been captured by two NASA missions and were presented in two separate studies in an announcement at NASA HQ in Washington today.

Using a mass spectrometer, the Cassini spacecraft detected an abundance of hydrogen molecules in water plumes rising from the “tiger stripe” fractures in Enceladus’ icy surface. Saturn’s sixth-largest moon is an ice-encased world with an ocean beneath. The researchers believe that the hydrogen originated from a hydrothermal reaction between the moon’s ocean and its rocky core. If that is the case, the crucial chemical methane could be forming in the ocean as well.

“Now, Enceladus is high on the list in the solar system for showing habitable conditions,” said Hunter Waite, leader of the Cassini Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer team at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio and lead author of the Enceladus study.

“The presence of hydrogen established another reference point saying there is hydrothermal activity inside this body, and that’s interesting because we know in our own oceans, those are very important places that are teeming with life, and they are probably one of the earliest places where life happened on Earth.”

Additionally, the Hubble Space Telescope showed a water plume erupting on the warmest part of the surface of Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons with an icy crust over a salty liquid water ocean containing twice as much water as Earth’s seas. This is the second time a plume has been observed in this exact spot, which has researchers excited that it could prove to be a feature on the surface.

“This is significant, because the rest of the planet isn’t easy to predict or understand, and it’s happening for the second time in the warmest spot,” said Britney Schmidt, second author on the Europa study.

Why is this exciting?

The necessary ingredients for life as we know it include liquid water, energy sources and chemicals such as carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur and phosphorus.

But we’ve also learned that life finds a way in the harshest of Earth’s environments, like vents in the deepest parts of the ocean floor. There, microbes don’t receive energy from sunlight, but use methanogenesis, a process that reduces carbon dioxide with hydrogen, to form methane.

Europa and Enceladus are showcasing some of these key ingredients for life in their oceans, which is why researchers believe they are the best chance for finding life beyond Earth in our own solar system.

Previous results from the Cassini mission’s flybys of Enceladus already had researchers intrigued. First, they could see plume material linked to interior water. They determined that the moon had a global ocean, and then a cosmic dust analyzer revealed silicon dioxide grains, indicating warm hydrothermal activity.

“This (molecular hydrogen) is just like the icing on the cake,” Waite said. “Now, you see the chemical energy source that microbes could use. The only thing we haven’t seen is phosphorus and sulfur, and that’s probably because they were in small enough quantities that we didn’t see them. We have to go back and look and search for signs of life as well.”

Earth is considered an ocean world because those bodies of water cover the majority of the planet’s surface. Other ocean worlds in our solar system, besides Europa and Enceladus, potentially include Jupiter’s moons Ganymede and Callisto; Saturn’s moons Mimas and Titan; Neptune’s moon Triton; and the dwarf planet Pluto.

It is believed that Venus and Mars were once ocean worlds, but the greenhouse gas effect and a vulnerable atmosphere, respectively, caused those planets to lose their oceans.

What’s next?

Although the Cassini mission, which began in 2004, comes to an end this year, Waite is eager for NASA to return to Enceladus and search for life, because he believes it is the best candidate for habitability.

Researchers want to confirm a very solid case for habitability by finding sulfur and phosphorus on Enceladus, as well as narrowing down the pH (potential of hydrogen) and reinforcing previous measurements. The second step would be looking for signs of life by flying a spectrometer through the plume, searching for rations of amino and fatty acids, certain isotopic ratios indicative of life and other relationships in molecules that indicate energy for microbial life, Waite said.

But first, we’re going to investigate Europa’s habitability.

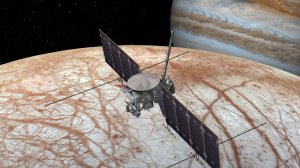

NASA plans to further explore ocean worlds in our solar system, including through the recently named Europa Clipper mission, the first to explore an alien ocean. Waite believes that Europa is currently at a disadvantage because a mass spectrometer hasn’t flown through its plume to collect data, and it’s Europa’s turn to have that experience.

Although Waite favors Enceladus of the two ocean worlds, Schmidt believes that Europa could be the best case for life in our solar system beyond Earth.

Schmidt, an assistant professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology’s School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, is also one of the architects of the project that became the Europa Clipper mission. She and two other researchers came up with the name while sitting in a hotel room during a conference.

The Europa Clipper, named for the innovative, streamlined ships of the 1800s, will launch in the 2020s and arrive at Europa after a few years.

“The reason we chose it is because the clipper ships were fast, American boats at the time that they were first used, when most shipping was achieved with large, slow vessels,” Schmidt said. “We liked clipper for that reason, an ingenious way to solve the Europa mission problem: How do you get a long-lived mission at Europa with global coverage but not be in the radiation environment?”

Because that region of the solar system traps atomic particles from the sun, the radiation of the area around Jupiter is dangerous to spacecraft.

Schmidt will be an investigator for the ice-penetrating radar instrument that will be housed on the Europa Clipper. It will act like an X-ray, peering through the unknown thickness of Europa’s icy crust the same way scientists use earthquakes to assess the interior of the Earth.

Other instruments will produce high-resolution images of the surface and measure the moon’s magnetic field, temperature, atmospheric particles and even the depth and salinity of the ocean.

Waite is using his knowledge from the Cassini mission to work on an improved mass spectrometer for the Europa Clipper mission.

“Cassini and Enceladus really allowed us to see the kind of things we could do with mass spectrometers and, more importantly, with material that’s coming up straight out of the ocean,” Waite said. “It’s a way of viewing the ocean without drilling into it. We didn’t necessarily have to land; we could sit there and and sample to study quite a bit about these ocean worlds just from flying through the material that comes out of the interior. That’s what the plumes are about on Europa as well. It’s that connection to the interior ocean.”

Europa or Enceladus?

Research suggesting the possibility of an ocean on Europa was published as early as 1977, after the Voyager mission saw long lines and dark spots, as opposed to a cratered surface similar to other moons. Then the Galileo mission reached Europa in 1996 and revealed for the first time that there was an ocean on another planet.

But because neighboring Mars has fueled imaginations and the possibility of exploring another planet for years, the general public hasn’t been as captivated by Jupiter’s moon. There are arguments that life could exist on Mars, but it was most likely habitable in the past, when it supported bodies of water and had a more hospitable climate and an atmosphere.

“The question is, do you want to study something that might have been habitable at one time, or do you want to study something that could be habitable right now?” Schmidt asked. “Europa has been pretty much Europa for 4.5 billion years, as long as the Earth has. So as far as what could have started and evolved there, that’s a compelling question.

“If you think about early Earth and early Europa, they were probably very similar, at least at the ocean interface. They are almost the same place at that point in time. That’s why I get excited about Europa. It could have been a place for life over the history of the solar system.”

Regardless of which of the two ocean worlds is the better candidate for hosting life, both researchers believe that exploring ocean worlds is one of the best things we can do.

“Understanding the diversity of our solar system is pretty important and the possibility of applying what we know here to exoplanets, it just opens up the range of possibilities for life beyond our previous expectations,” Waite said.

“These ocean worlds all over the outer solar system that are a little bit alien,” Schmidt said, “they’re the most compelling things that we have in the solar system.”