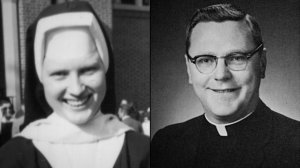

The exhumation of a Catholic priest’s body by Baltimore County Police could hold the key to solving the 47-year-old cold case of a murdered nun.

On February 28, police opened the grave of Rev. A. Joseph Maskell after securing an order from the state’s attorney, according to Elise Armacost, director of public affairs for Baltimore County Police.

Police took DNA samples from the corpse to check against a DNA profile developed from evidence taken in 1970 from the scene in Maryland where the badly decomposed body of Sister Catherine Ann Cesnik had been found by a father and son out hunting. The 26-year-old nun had been missing for nearly two months.

In the decades since the nun’s killing and as DNA testing has become a vital investigative tool, Baltimore County police have compared the DNA of several other people as part of their investigation into the never-closed case, according to Armacost, but those tests did not match the DNA profile from 1970.

The current team of cold case detectives, assigned the Cesnik case in 2016, began discussing the exhumation of Maskell almost immediately, but it took time to get proper authorization.

“Determining whether Maskell’s DNA matches the evidence remaining from the crime scene is a ‘box’ that must be checked,” said Armacost.

Now, police are awaiting results of DNA from the body of Maskell, a priest who was accused in the 1990s of sexually assaulting young women. They are waiting to learn if those results link Maskell to the death of a nun who, according to an attorney, was a confidant to young women who had been assaulted by the priest.

Sexual assault allegations against the priest

In the 1990s, sexual assault and abuse allegations began to surface against Maskell, who had served as a chaplain at Archbishop Keough High School in Baltimore. In 1992, two female former students came forward to say Maskell abused them. By 1994, they and several other students had filed a lawsuit alleging physical and sexual abuse by Maskell through the 1960s and 1970s, according to Armacost.

Sean Caine, spokesman for the Archdiocese of Baltimore, said the archdiocese removed Maskell from his post as soon as they learned of the allegations in 1992, in order to conduct their own investigation. He was permanently removed from the ministry in 1994. While police were never able to bring charges against the priest, Caine said that 16 people who said Maskell abused them have since received money from the archdiocese as part of financial agreements.

According to Armacost, in 1994 one of the students who claimed abuse by Maskell when she was in high school said that he took her to a remote dumping area and showed her Cesnik’s decaying body as a warning of what would happen if she told anyone about him.

Joanne Suder, an attorney for many of Maskell’s sexual abuse victims, said, “If law enforcement, in general, had done their job back in 1970, they’d have brought Maskell in then and this would have all been necessary in 2017.”

“There’s no question that my clients told Sister Cathy (Cesnik) what was going on,” Suder said. “There’s no question she told them she would do something about it.”

According to Armacost, Baltimore County police in 1994 took the alleged victim’s statement seriously and interviewed Maskell, himself once the chaplain for the Baltimore County Police and other area law enforcement agencies. But investigators found only a few inconsistencies in some statements, and detectives were unable to find any damning evidence against the priest.

Maskell was never charged.

“(Cesnik) was a nun. The church was her life and the people important to her were in the church,” said Armacost. “The theory that she was killed because she knew something about abuse that was going on by priests within the church continues to be a theory, but is not the only theory. It continues to be one of several theories.”

By 1994, Maskell no longer worked at the high school and was the pastor of Holy Cross Church in Baltimore. When he was removed from the ministry he fled to Ireland, where he lived for a time before returning to the Baltimore area, according to police. He died in 2001, police said.

An alternate theory

Cesnik was 26 and on a sabbatical from the Roman Catholic Church. She had moved to an apartment outside the convent with another nun and began teaching at Western High School in Baltimore on November 7, 1969, when she left her apartment to run an errand at Edmondson Village Shopping Center in Baltimore, according to Armacost. When she didn’t come home, her roommate reported her missing the next day.

Her body was found in Lansdowne, south of Baltimore, on January 3, 1970. An autopsy found Cesnik died from blunt force trauma to the head, according to police. Her case has remained open ever since, Armacost said.

One of Baltimore’s most infamous cold cases, Cesnik’s death is the subject of a new documentary series, “The Keepers,” which releases May 19 on Netflix.

Armacost says the timing of Maskell’s exhumation has nothing to do with the documentary, and opening the priest’s grave was simply a step that cold-case investigators felt needed to be taken to leave no stone unturned.

Police have also looked into whether Cesnik’s death is related to the deaths of three other young women in the Baltimore area around the same time.

According to police, Joyce Helen Malecki, 20, disappeared from a shopping mall only days after Cesnik on November 11, 1969, in Glen Burnie, a suburb of Baltimore.

Pamela Lynn Conyers, 16, was last seen at the shopping mall in Glen Burnie on October 16, 1970, police said.

Grace Elizabeth Montanye, 16, met a stranger at a shopping mall on Sept 29, 1971 in south Baltimore, according to police.

They were all young, attractive women, police said, who looked similar. They were last known to be headed to or last seen at shopping centers in the area, the same as Cesnik.

Each of their bodies was found in different law enforcement jurisdictions, delaying any connections from being made for many years, according to Armacost. None of these cases have been solved.