On January 17, 1994, the ground under Los Angeles violently shook as a magnitude 6.7 earthquake centered in the San Fernando Valley hit the region.

Damage was catastrophic as tens of thousands of buildings cracked or collapsed entirely. Freeways buckled and at least 57 people lost their lives in the immediate aftermath of what became known as the Northridge Earthquake.

At the time, L.A. hadn’t experienced an earthquake of that magnitude in 23 years, and it has now been 30 years since the Northridge quake.

Does this mean Southern California is overdue for another major earthquake?

The U.S. Geological Survey says the probability of a magnitude 6.7 quake hitting the L.A. area again within 30 years is 60%. There’s a 46% chance of a magnitude 7.0 and a 31% probability of a magnitude 7.5, USGS says.

So the likelihood of another Northridge-sized quake happening in the coming decades is, unfortunately, strong.

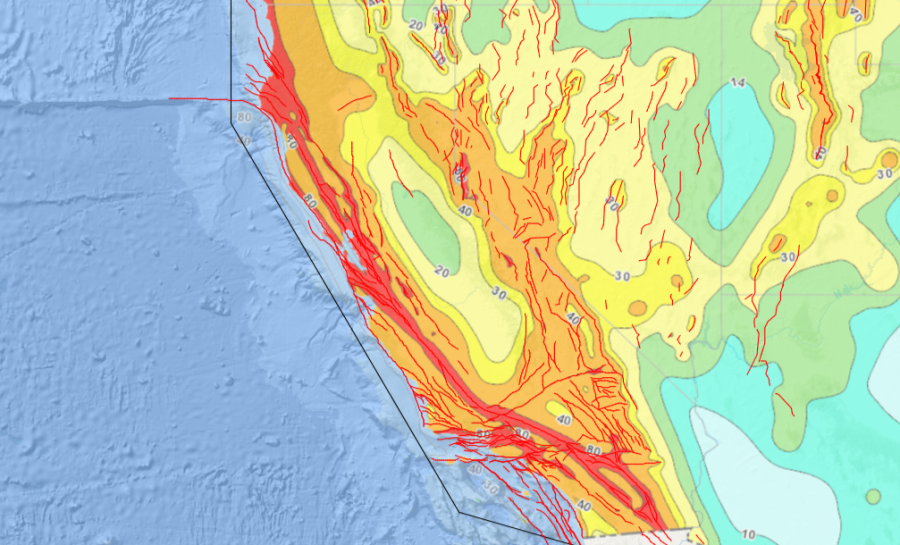

The 1994 earthquake occurred along a small, previously undiscovered fault. The greater concern, says world-renowned seismologist Dr. Lucy Jones, is the 800-mile-long San Andreas Fault, which has already been responsible for many of California’s largest quakes.

“[Northridge] wasn’t ‘The Big One,’” Jones recently told KTLA 5 News anchor Frank Buckley. “When the San Andreas [Fault] goes, we’re going get that level of shaking instead of over just the San Fernando Valley … It will be a ten, 20, 50 times larger area that will receive the strongest level of shaking. That’s the difference with a bigger earthquake is a longer fault.”

Both the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and 1989’s Loma Prieta quake occurred along the San Andreas Fault and had devastating impacts on the Bay Area.

In Southern California, where it terminates at the Salton Sea, experts say the San Andreas Fault produces quakes at an interval of roughly every 150 years – only there hasn’t been one in at least 300 years.

Despite the gap, Dr. Jones doesn’t believe this means there is imminent danger.

“We have a much better understanding of the physics of earthquake faults today,” she said. “It’s a much more random process over time. If we went 10,000 years without an earthquake then yes, we’d have to have one. But at just twice the average [of 300 years], that’s just the random distribution that we see.”

Dr. Jones says Southern California is better prepared for a large earthquake today than 1994 due to seismic retrofitting and improvements in building and road construction. If or when “The Big One” occurs, she says most people will survive.

Her greater concern is the economic and social fallout.

“We have seen communities really destroyed by these types of disasters. People leave and go elsewhere … Whether our community comes out on the other end okay is much more debatable.”