A skeleton found by hikers this fall near California’s second-highest peak was identified Friday as a Japanese American artist who had left the Manzanar internment camp to paint in the mountains in the waning days of World War II.

The Inyo County sheriff used DNA to identify the remains of Giichi Matsumura, who succumbed to the elements during a freak summer snow storm while on a hiking trip with other members of the camp. Matsumura had apparently stopped to paint a watercolor while the other men, a group of anglers, continued toward a lake to fish.

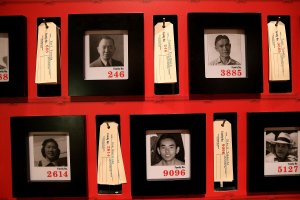

His body wasn’t found for another month, and the tragedy was overshadowed in the immediate days after his Aug. 2, 1945 disappearance when the U.S. dropped the first atomic bomb, hastening Japan’s surrender in the war. Matsumura was one of more than 1,800 detainees who died in the 10 prison camps in the West, though it’s one of the more unusual deaths.

While his burial in the mountains was well known among members of the camp and his family, the story faded over time and the location of the grave site in a remote boulder-strewn area 12,000 feet above sea level was lost to time.

Lori Matsumura, the granddaughter who provided the DNA sample, was surprised when Sgt. Nate Derr of the Inyo County sheriff’s office contacted her to say they believed her grandfather’s remains had been discovered. After all, he had been found nearly 75 years ago and buried.

“It was a bit of a rediscovery,” she told The Associated Press. “We knew where he was approximately because we knew the story of what happened. So we knew he was there.”

As a girl, she was haunted by a photo her grandmother showed her of the pile of stones where her grandfather was buried beneath a small marker in the remote mountains.

“Once in a great while, she would bring it out and say, ’Oh, this is all they could bring of your grandfather.’ And my aunt would be, ‘No, don’t show her that picture,’ ” Matsumura said. “It did scare me. I’m like, ‘Oh, my God, that’s my grandfather under there.’”

Her aunt, Kazue, told her that her grandfather was known as “the ghost of Manzanar.”

“To this day, it seems like he’s not passed away,” Kazue, who died two years ago at 83, told the Manzanar National Historic Site. “It seems like he’s gone someplace, because I didn’t see his body.”

It was by accident on Oct. 7 that Tyler Hofer and a friend stumbled upon the remains on their way to the top of Mount Williamson. The two were off course on a crude route through the jumble of granite boulders in a basin of lakes when Hofer looked down and saw what looked like a bone.

Earlier in the day, the men had discovered a pile of bones beneath Shepherd Pass, where a herd of migrating deer had plummeted to their death two years earlier on a steep, icy slope. At first, Hofer thought the bone was more animal remains, but upon closer inspection he realized it was a human skull.

Hofer and Brandon Follin moved the rocks and found an intact skeleton with a belt around its waist and leather shoes on the feet. The arms appeared to be crossed over the chest.

Hofer posted about his finding on a Facebook forum, describing inaccurately that the skull appeared to be fractured and the shoes were the type worn by rock climbers. He suggested it was a case of foul play.

When contacted by the AP, the sheriff’s office said there were no signs of a crime. They said it was a mystery, though, because they had searched records of missing reports going back decades and said no one was known to be lost in the area that would fit that description.

What officials didn’t say, though, was that by the time they had retrieved the bones by helicopter, they already had a hunch it might be Matsumura.

While his story was little known, it got renewed attention when “The Manzanar Fishing Club” documentary film came out in 2012. Director Cory Shiozaki told the story about intrepid prisoners who would escape from the camp at night and slip into the mountains to fish for trout — sometimes for weeks at a time.

A segment of the film on Matsumura’s death didn’t make the final cut. Still, Shiozaki often addressed the tragedy at the many screenings where he spoke and the story became more broadly known.

In the final year of the war, the guard towers were no longer manned with armed soldiers, and people were free to leave the camp. The Matsumuras, like many others, had no home or business to return to, so they remained behind.

When a group of fishermen planned to hike to the chain of lakes in Williamson Bowl, Matsumura insisted on tagging along.

The trip leader didn’t want Matsumura, 46, to join them because he was older and not in great physical shape, but he eventually relented, Shiozaki said. The group of six to 10 men headed into the Sierra Nevada on July 29, 1945.

At some point in the demanding trek, Matsumura stopped to paint a water color and said he would catch up later. A freak snowstorm blew in, and the fishermen retreated to a cave.

When the weather cleared, they searched fruitlessly for Matsumura. Three later search parties from the camp also failed to find him.

During that period, his wife, Ito, worried so much that her hair turned the color of snow, according to Kazue, who was 10 at the time.

“I felt sorry for my mom, you know,” Kazue told the National Park Service. “She couldn’t eat or anything … She had black hair, and it turned white all of a sudden.”

Matsumura’s decomposing remains were found a month after he was lost by hikers from the nearby town of Independence.

Members from the camp then hiked back up to bury him in a mountainside grave under a sheet his wife provided, according to the park service. Atop the granite stones placed on his body, was a granite column with a paper note attached to mark the site. In Japanese characters, it gave his name, age and said, “Rest in Peace.”

The burial party brought back clippings of his hair and fingernails, a Buddhist tradition when a body can’t be returned, for a ceremony at the camp.

Rather than reopen an old wound in her family’s past, the finding has awakened interest in learning more about their story and time in the camp and sharing it with nephews and nieces, Lori Matsumura said.

Until she recently saw a photo of the search party, Lori Matsumura never knew her father, Masaru, had played a role in looking for his dad.

Her father never talked about the experience, and she now regrets not pressing him for more information. Like many who endured the hardship and humiliation of the one of the darkest chapters of U.S. history when more than 110,000 people of Japanese descent — two-thirds American citizens — were imprisoned because of fear they would remain loyal to their ancestral homeland, Masaru Matsumura seemed bitter and rarely spoke of camp, Lori Matsumura said.

He had been close to graduating from high school when his family was sent to Manzanar. After his father’s death, Masaru Matsumura had to support his mother and three siblings when they returned to Santa Monica. He had to take a job as gardener as his father had done.

Kazue Matsumura said her mother, widowed at 43, worked two or three jobs, according to the oral history she gave Manzanar.

Ito Matsumura was 102 when she died in 2005. She was buried with a lock of her husband’s hair and his name on her gravestone.

Most of what Lori Matsumura knows of the camp came from her grandmother and an aunt who lived across the street from the little home where she grew up in Santa Monica.

Now that her curiosity has been sparked, Lori Matsumura has no one to ask about their experiences in camp or the impact of her grandfather’s death on the family. Her father died last summer at age 94, the last of his generation.

“I wished I would have dug a little deeper and found out more stories from my dad,” she said. “He didn’t talk about it much. I wished I would have asked more questions.”