Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price announced Tuesday that President Donald Trump has no immediate plans to declare the nation’s opioid epidemic a public health emergency, a decision that flies in the face of the key recommendation by the President’s bipartisan opioid commission.

Public health experts had said that an emergency declaration was much needed in turning the tide to save American lives. The commission, headed by New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, was resolute in maintaining the importance of an emergency declaration: “Our citizens are dying,” it said.

“We say to the president, you must declare an emergency,” Christie said on CNN last week.

Price sought to minimize the administration’s decision Tuesday, just after Trump said that a stronger law enforcement response is needed and that he is committed to combating the problem.

“The president certainly believes that we will treat it as an emergency — and it is an emergency,” Price said.

Trump just won’t declare it an emergency, he explained.

“We believe that at this point, the resources that we need or the focus that we need to bring to bear to the opioid crises can be addressed without the declaration of an emergency,” Price said, “although all things are on the table for the president.”

He emphasized that he’s working with agencies across the Cabinet on a strategic prevention, treatment and recovery plan and that the president was briefed and fully on board. He said Trump “made certain that we understood he was absolutely committed to making certain that we turn this scourge in the right direction.”

“It’s a problem the likes of which we have never seen,” Trump said earlier in the day at his New Jersey golf club.

Christie did not respond to requests for comment.

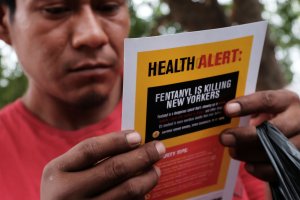

Since 1999, the number of American overdose deaths involving opioids has quadrupled, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says. From 2000 to 2015, more than 500,000 people died of drug overdoses, and opioids account for the majority of those. The commission said 142 Americans die from drug overdoses every day — a toll “equal to September 11th every three weeks.”

In addition to the emergency declaration, the commission recommended rapidly increasing treatment capacity for those who need substance abuse help; establishing and funding better access to medication-assisted treatment programs; and equipping all law enforcement with naloxone, the opioid antidote used by first responders to save lives.

Commission member Bertha Madras, a researcher at Harvard Medical School and McLean Hospital in Massachusetts, sought to downplay the administration’s decision Tuesday.

“All that matters is whether timely and considered recommendations can and will reverse this calamitous trend,” Madras wrote in an email. “Nomenclature will not solve this complex problem. Wise policies and action plans are the more relevant issue.”

Madras added that Price and Trump are “highly committed to reducing the problem and are fully aware that timely implementation of sound and effective policies is the next phase.”

New government data show an increase in opioid overdose deaths during the first three quarters of last year, an indication that efforts to curb the epidemic are not working.

Declaring a public health emergency would make the opioid epidemic the government’s top priority, infusing much-needed cash into hard-hit areas and bolstering resources.

“It means every state health department, local government and the federal government would treat this as the top priority,” said Dr. Guohua Li, a professor of epidemiology and anesthesiology at Columbia University who has studied the epidemic for over a decade

It is not often that a public health emergency is declared for something other than a natural disaster. The US Department of Health and Human Services declared one in Puerto Rico last year after more than 10,000 Zika cases were reported there. Before that, the last emergency declaration, unrelated to a natural disaster, was during the 2009-10 flu season, when there was widespread concern over a potential pandemic.

Dr. Arthur Reingold, a professor of epidemiology at the University of California-Berkeley, worked with the World Health Organization on giving advice and helping stockpile vaccines during the H1N1 pandemic in 2009. It was that type of global initiative that helped curb the spread of bird flu.

The crucial thing an emergency declaration does, he said, is mobilize resources and bring much-needed attention to the problem, especially in getting politicians, leaders and the public on the same page.

“Typically, humans don’t get motivated until there’s actually a problem,” Reingold said. “In this case, this is a problem that has been festering for some time — and now we’re finally paying attention to it.”

Alberto de la Vega, a doctor at the University of Puerto Rico who evaluated more than 1,000 pregnant patients with Zika, said the emergency declaration last year “definitely helped.”

“We definitely received a benefit from the classification and receiving more funds. There’s no question about it,” de la Vega said. “But the bureaucracy in making those allocation of funds reach us, always comes later than we wish.”

Some public health experts fear that an “incarceration-first” approach would only renew failed policies of the past.

“We need to be cautious about the intentions of this administration,” said Grant Smith, deputy director of national affairs for the nonpartisan nonprofit Drug Policy Alliance. “Declaring a national emergency could be used to further the war on drugs. It could give the administration leverage to push for new sentencing legislation or legislation that enhances drug penalties or a law enforcement response.”

Trump said Tuesday that the previous administration was too lenient and didn’t do enough to prosecute drug offenders: “We’re not going to let it go.” He also advocated for more abstinence-based treatment.

“The best way to prevent drug addiction and overdose is to prevent people from abusing drugs in the first place. If they don’t start, they won’t have a problem.”