As tourists stroll between Yellowstone’s 300 active geysers, taking selfies in front of thousands of bubbling, boiling mud pots and hissing steam vents, they are treading on one of the planet’s greatest time bombs.

The park is a supervolcano so enormous, it has puzzled geophysicists for decades, but now a research group, using seismic technology to scan its depths, have made a bombshell discovery.

Yellowstone’s magma reserves are many times greater than previously thought, say scientists from the University of Utah.

Underneath the national park’s attractions and walking paths is enough hot rock to fill the Grand Canyon nearly 14 times over. Most of it is in a newly discovered magma reservoir, which the scientists featured in a study published on Thursday in the journal Science.

It may help scientists better understand why Yellowstone’s previous eruptions, in prehistoric times, were some of Earth’s largest explosions in the last few million years.

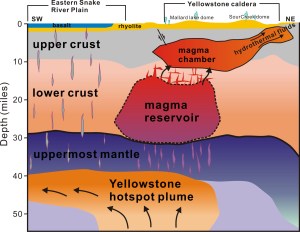

The Utah scientists also created the first three-dimensional depiction of the geothermal structure under Yellowstone, which comprises three parts.

Fire in Earth’s belly

Yellowstone’s ultimate heat source reaches down 440 to 1,800 miles beneath Earth’s surface — and may come from its molten core. It is responsible for fueling the newly discovered reservoir that lies on top of it.

The magma chamber, which scientists already knew about, lies on top of the reservoir — and draws magma from it. It is a three to nine miles under the surface of the Earth and is what fuels the geysers, steaming puddles and other hot attractions.

It alone has a volume 2.5 times that of the Grand Canyon.

But those great magma expanses do not mean that the two hellish hollows could overflow the Grand Canyon with molten rock.

No new dangers

The overwhelming bulk of their magma cavities comprise scorching — yet solid — rock, which is hollow, like sponges, and filled with pockets of liquefied rock.

Also, the discovery doesn’t mean that there is now more magma than there was before, the scientists say. And they are no signs of an imminent eruption.

“The actual hazard is the same, but now we have a much better understanding of the complete crustal magma system,” said researcher Robert B. Smith.

An eruption in the next few thousand years is extremely unlikely, the USGS says. The Utah scientists put the yearly chance at 1 in 700,000 — about the odds that you will be struck by lightning.

World’s greatest explosions

But when it does blow, it probably will change the world.

Compared to Yellowstone’s past, Mount St. Helens was a picnic, when it covered Washington state with an ash bed about the size of Lake Michigan in 1980. Mount Pinatubo, which exploded in the Philippines in 1991, doesn’t begin to scratch the surface of Yellowstone’s roar.

Nor did Krakatoa in 1883, which killed thousands, and the final explosion of which reportedly ruptured the eardrums of people 40 miles away.

To understand the consequences of Yellowstone’s previous eruptions, open the history books to 1815, when Mount Tambora blew many cubic miles of debris skyward and killed about 10,000 inhabitants of Indonesia in an instant, according to a report in Smithsonian Magazine.

Its dust may have blocked sunlight around the world, chilling the air and dropping the Earth’s climate into a frigid phase that garnered the year 1816 the “year without a summer,” some climatologists believe. It may have led to frosty crop failures in Europe and North America.

Magnitudes worse

Tambora blew 36 cubic miles of debris into the sky. Yellowstone has dwarfed that at least three times, the USGS says.

The explosions have left deep scars, and park goers often become familiar with one — the Yellowstone Caldera, which takes up much of the park and is lined by a roundish mountainous ridge.

The caldera is a volcanic crater some 40- by 25-miles large, left behind when 240 cubic miles of debris ruptured out of the Earth and into the air during volcanic discharge some 630,000 years ago, USGS says.

Lava flowed into the breach, filling it, which may account for the lack of a deeper crater.

Long before that, 2 million years ago, volcanic activity blew 600 cubic miles of Yellowstone debris into the air.

Those were the two largest eruptions in North America in a few million years, the USGS said, and they each buried in ash more than a third of what is now the continental U.S.

“If another large caldera-forming eruption were to occur at Yellowstone, its effects would be worldwide,” the USGS says. It would drastically effect the world’s climate.

Keeping an eye out

So, it’s no wonder scientists have cast an eye on Yellowstone for a while.

The Utah researchers gave the Yellowstone’s magma bowels a sort of CT scan, said lead researcher Hsin-Hua Huang. Volcanic activity triggers 2,000 to 3,000 small earthquakes per year, and the shake and shock waves travel at different speeds through molten, hot and other rock.

It allowed them to develop a detailed model of the seething expanse beneath Yellowstone that makes it what it is. Here are the upper magma chamber and lower magma reservoir by the numbers.

The upper chamber, which caused the historic blasts and is closest to the surface, is 2,500 cubic miles in volume and measures about 19 by 55 miles. The lower reservoir, which has a volume of 11,200 cubic miles, measures about 30 by 44 miles and is about 16 miles thick.

Even if the next explosion is many thousands of years away, Yellowstone’s cavernous heat tanks poke up an occasionally surprise. The last lava flow was some 70,000 years ago, USGS says.

But more recently in 2003, ground temperatures rose high enough to dry out geysers and boil the sap in some trees. A few inches under the surface, thermometers recorded a temperature of 200 degrees Fahrenheit — nearly hot enough to boil water.

So, national park authorities closed Yellowstone to keep people from burning their feet — or basting their tires on melting roads.