Muhammad Ali, the legendary boxer who proclaimed himself “The Greatest” and was among the most famous and beloved athletes on the planet, died Friday surrounded by his family at a hospital in Phoenix, Arizona, a family spokesman said.

He was 74.

Ali had been at a Phoenix hospital since Thursday with what spokesman Bob Gunnell had described as a respiratory issue.

The death of the iconic athlete was confirmed in a statement issued Friday night by Gunnell who thanked the public for their thoughts and prayers and asked for privacy.

“After a 32 year battle with Parkinson’s disease, Muhammad Ali has passed away at the age of 74. The three-time World Heavyweight Champion boxer died this evening,” the statement said.

Ali was diagnosed with the disease in 1984, three years after he retired from a boxing career that began when a skinny 12-year-old Louisville, Kentucky, amateur put on the gloves.

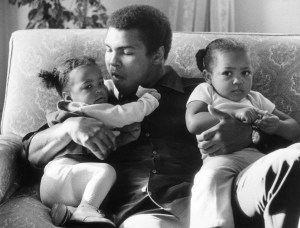

He is survived by his nine children, including daughter Laila, who like her father became a world champion boxer; and his fourth wife, Lonnie.

Hours before her famed father passed away, Laila Ali posted a throwback photo of Muhammad Ali with her daughter, Sydney, who was born in 2011.

“I love this photo of my father and my daughter Sydney when she was a baby! Thank for all the love and well wishes. I feel your love and appreciate it!!” Laila Ali wrote.

Since the mid-1960s, he had been one of the most famous faces on Earth, and even though his appearances in recent years were few, the name Muhammad Ali still sparked smiles all around the globe.

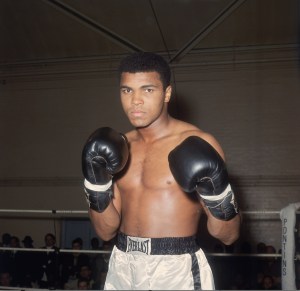

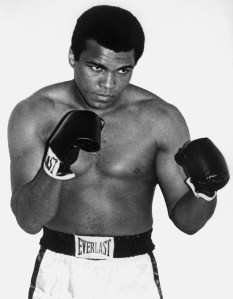

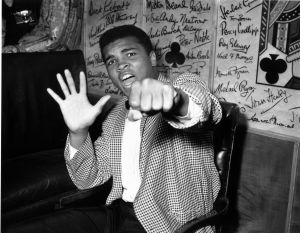

Ali was known in the ring for his flashing hand speed — unusual for a heavyweight — for his showmanship and also for his brashness and braggadocio when a microphone was put before him. He taunted opponents before matches, trash-talked them during and proclaimed his greatness to reporters afterward.

His hands and his mouth were furiously fast. His skill as a boxer made him “The Greatest” in his mind and in the minds of many others.

He antagonized opponents with his taunts, amused reporters with his boasts and angered government officials with his anti-war speeches. At the same time, he goaded a stubborn, hard-nosed society with his stinging jabs against pervasive racism.

He stayed on his toes, literally, during a bout, sometimes quickly moving his feet forward and backward while his upper body stayed in place. The mesmerizing move became known as the “Ali Shuffle.”

Fans on every continent adored him, and at one point he was the probably the most recognizable man on the planet.

But he also was a controversial figure at home, announcing his conversion to Islam and name-change after an upset title win over Sonny Liston, then refusing to enter the draft for the Vietnam War and publicly speaking about racism in the United States.

In youth, told he’d better learn to box

Ali was born January 17, 1942, in Louisville as Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. His interest in boxing began at age 12, after he reported a stolen bike to a local police officer, Joe Martin, who was also a boxing trainer.

Martin told the young, infuriated Clay that if he wanted to pummel the person who stole his bike, he had better learn to box.

Over the next six years, Clay won six Kentucky Golden Gloves championships, two National Golden Gloves championships and two National Amateur Athletic Union titles.

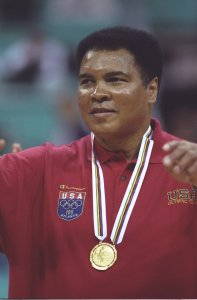

Just months after he turned 18, Clay won a gold medal as a light heavyweight at the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome, convincingly beating an experienced Polish fighter in the final.

The story goes that when he returned to a hometown parade, even with the medal around his neck, he was refused service in a segregated Louisville restaurant because of his race. According to several reports, he threw the medal into a river out of anger. The story is disputed by people who say Ali misplaced the medal.

Thirty-six years later, he was given replacement medal and asked to light the cauldron at the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, something he said was one of the greatest honors in his athletic career.

Clay turned professional after the Olympics and quickly won 19 straight fights. For many of them Clay, then known as “The Louisville Lip,” would make a rhyme to predict what round his opponent would fall.

The underdog stings like a bee

For his first heavyweight title fight, against the brutish Liston, he went a step further, renting a bus, and on the day he signed to fight the champ he went by Liston’s home.

On the side of the bus was painted: “World’s Most Colorful Fighter” and “Liston Will Go In Eight.” To make sure he was heard, Clay used a megaphone and shouted from an open window.

And in the lead-up to the fight, Clay, flanked by corner man Drew “Bundini” Brown, uttered the famous phrase that followed him forever, “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.” (Often missed is the subsequent line, “Rumble, young man, rumble.”)

In stark contrast to Clay’s pretty-boy image, Liston — a formidable and domineering fighter — had an extensive criminal past. He learned to box in prison. But the young, brash Clay appeared supremely confident, and his mocking of Liston was relentless.

“The crowd did not dream when they laid down their money that they would see the total eclipse of the Sonny,” he said.

Despite the 7-to-1 odds against him, Clay defeated Liston in seven rounds to become heavyweight champion of the world.

He later told CNN’s Nick Charles that, despite his bravado, he was “scared to death.”

“I just acted like I wasn’t,” he said.

Post-Liston: From Cassius X to Muhammad Ali

The day after the Liston fight, Clay announced that he had joined the Nation of Islam and was changing his name to Cassius X, the letter symbolizing the unknown name taken away from his family by slave owners hundreds of years before.

A year later, he was anointed Muhammad Ali by Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad. Most sportscasters initially refused to call him by his new name. But Howard Cosell did, becoming a supporter and friend to the champ as they verbally sparred for the rest of Cosell’s life.

Once Cosell said Ali was being truculent.

Ali snapped back, “Whatever truculent mean, if that’s good, I’m that.”

Many in the United States scorned Ali’s name change and his alignment with the Nation of Islam, and a furor erupted after he refused because of his religious beliefs to serve in military during the Vietnam War when he was called up in 1966.

“I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong,” Ali said. “No Vietcong ever called me n—-r.”

At the weigh-in before one of his last fights of 1967, his opponent, Ernie Terrell, called him “Clay.”

A furious Ali trounced Terrell in the ring while yelling “What’s my name?” A month later, Ali knocked out Zora Folley.

But, at the peak boxing age of 26, he began a forced three-and-a-half-year exile from championship boxing.

The conscientious objector

Almost as quickly as Ali had arrived, his World Boxing Association heavyweight title was gone, revoked after he claimed conscientious objector status in refusing the draft. He also was stripped of his passport and all of his boxing licenses. He faced a five-year prison term after losing an initial court battle defending his objection to serving in a war that he called “despicable and unjust.”

Ali lost the chance at tens of millions of dollars in endorsements while appealing his case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

During this time, Ali aligned himself with Nation of Islam leaders including Malcolm X, making him even more of a controversial figure as well as a household name.

He earned a living during his hiatus from boxing by speaking against the Vietnam War on college campuses, one of the first national figures to verbally oppose the war.

“What was so important about it was that in a war in which young black men, mainly without any money and with little education, were dying in disproportionate numbers and being shipped off to Southeast Asia in disproportionate numbers, the symbol of strength, the symbol of vitality and virility, this young black man — outspoken — stands up and says no,” explained David Remnick, author of “King of the World,” a book about the young boxer.

Back to the ring — and on to Joe Frazier

The anti-war sentiment had gathered momentum by 1970, when a judge ruled that Ali could box professionally. When Ali made his return to the ring, he discovered that the long absence had left a marked effect on his skills.

He quickly dispatched Jerry Quarry in his first fight back, but had a rough 15-round go with Oscar Bonavena before he got a chance to get his title back.

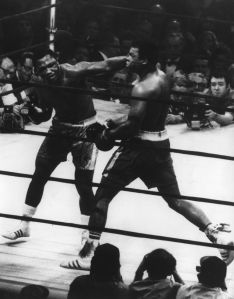

In 1971, he and his perfect record met undefeated champion Joe Frazier in an epic battle that boxing writers have dubbed “The Fight of the Century.” Each man was guaranteed $2.5 million, at that time the biggest boxing payday in the sport, with an estimated 300 million viewers worldwide.

Their rivalry would become legend and intensely personal, with constant verbal taunting from Ali.

“I’ll be the ghost that haunts boxing,” he said. “People will say, ‘Ali is the real champ, and everyone else is a fake,’ ” Ali said of Frazier.

Ali also hurled racial insults at Frazier, calling him an “Uncle Tom” and a black man disguised as a Great White Hope, a phrase that Frazier later said infuriated him.

And Ali delighted the media when he proclaimed, “Joe is going to come out smoking, but I ain’t going to be joking. I’ll be pecking and a-poking, pouring water on his smoking. This might shock and amaze ya, but this time I’ll retire you, Frazier.”

The world would soon learn that even the man who called himself “The Greatest” had his struggles. The match began with both fighters engaging in a series of powerful punches and counterattacks. In the 15th round, Frazier unleashed a devastating left hook that floored Ali.

It would be only the third time Ali had been knocked down in his career. When the final bell rang, the judges awarded Frazier a 15-round decision, sending Ali to his first loss in 32 professional fights.

Months after the defeat, Ali got a major victory outside the ring when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld his conscientious objector claim. His passport and his boxing licenses were reinstated, and the threat of prison time was erased.

Over the next few years, Ali’s religious views turned him more toward Sunni Islam, and he rejected many of the teachings of the Nation of Islam.

He won a 1974 rematch with Frazier, earning another shot at the heavyweight title, which would turn out to be the fight of his career and one of the most memorable events in sports history.

Foreman, Zaire and ‘The Rumble in the Jungle’

“The Rumble in the Jungle” pitted Ali against fearsome champion George Foreman, a 3-to-1 favorite to win the match in central Africa. Boxing promoter Don King had struck an agreement with the government of Zaire to guarantee the unheard-of sum of $10 million for the boxers.

Ali adapted his trademark phrase by telling reporters he would “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee, his hands can’t hit what his eyes can’t see.”

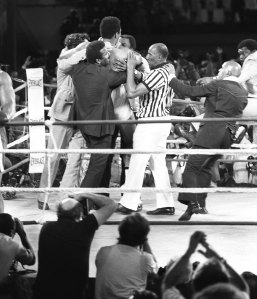

Instead, in what is considered to be his best tactical fight, Ali used the “rope-a-dope” technique, leaning far back on the ropes, absorbing Foreman’s punches with his gloves and arms and letting the heavy puncher tire out.

All throughout the fight, the throng of fans chanted: “Ali bomaye! Ali bomaye!” which means “Ali, kill him!”

In the eighth round, Foreman swiped at Ali in one corner for more than a minute until a stinging series of Ali right hands sent Foreman to the ground and brought a boisterous roar from the people watching.

The next year, Ali defeated Frazier again in the Philippines, the famous “Thrilla in Manila,” after 14 grueling rounds.

A damaged champ’s career winds down

He retained his title as heavyweight champ until 1978, when he lost in a shocker to the inexperienced Leon Spinks. After defeating Spinks in a rematch, he regained the title for a record third time, only to give it up when he announced a short-lived retirement in 1979.

He came back the next year at age 38, when he challenged Larry Holmes, hoping to capture a fourth heavyweight title. He lost by a technical knockout.

According to Thomas Hauser, who wrote an authorized biography of the boxer in 1991 and had access to his medical records, Ali should never have been allowed to enter the ring against Holmes.

Ten weeks before the match, a team of doctors at the Mayo Clinic submitted a medical report to the Nevada State Athletic Commission describing a small hole in his brain’s outer layer and noting that the boxer reported a tingling sensation in his hands and slurred speech.

Ali retired permanently in 1981 with a career record of 56 wins — 37 by knockout — against five losses.

Ed Schuyler, a boxing columnist for The Associated Press who covered Ali’s career, said his boastful statements were not far from the truth.

“He would just work on you — work on you, work on you — and he let an opponent know from the day one that he was the man, and the other guy had no shot, and he was lucky that he was even there,” Schuyler said.

Parkinson’s, and ‘a relentless effort to promote peace’

In the years to follow his retirement, Parkinson’s disease began to take away Ali’s motor skills and his ability to speak coherently, but he never strayed from the spotlight.

“Even though Muhammad has Parkinson’s and his speech isn’t what it used to be, he can speak to people with his eyes. He can speak to people with his heart, and they connect with him,” wife Lonnie Ali said.

She said doctors told her the disease was not the result of absorbing too many punches but a genetic condition.

Ali’s fame transcended the boxing ring, and he used that fame toward what his daughter Hana Ali called “a relentless effort to promote peace, tolerance and humanity around the world.”

He was welcomed by American presidents and foreign dictators, including Iraq’s Saddam Hussein and Cuba’s Fidel Castro.

His role as an ambassador of peace started in 1985, Hana Ali said, when he traveled to Lebanon to try to secure the release of four American hostages. In 1990, he was credited with securing the release of more than a dozen American hostages from Iraq just days before the start of the Persian Gulf War and was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1997.

He also used his notoriety for charity work, helping raise millions of dollars for food and medical relief around the world. In 1998, he was named a United Nations Messenger of Peace.

“Muhammad feels that everything he did prior to now was to prepare him for where he is now in life,” Lonnie Ali said. “He is very much more a spiritual being. He is very aware of his time here on Earth. And he has sort of planned the rest of his life to do things so that he is assured a place in heaven.”

One of Ali’s last triumphs was the construction of a state-of-the-art museum chronicling his life and promoting peace and tolerance around the world.

His vision became a reality in 2005, when the Muhammad Ali Center opened in his hometown of Louisville, a place he called “the greatest city in the world.”

Inside the cultural center and museum, Ali’s voice can be heard from plasma screens, reminding those who tried to defeat him that his claim of being “The Greatest” lived up to reality:

“Ali’s got a left; Ali’s got a right. If he hits you once, you’re asleep for the night. And as you lie on the floor, while the man counts 10, hope and pray that you never meet me again.”