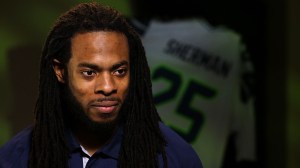

There are two Richard Shermans.

There’s the smart Stanford graduate who loves to read. And there’s the brash, trash-talker who considers himself the best NFL player.

One is quiet, reflective. The other can be loud — very loud.

Much of America met the second Richard Sherman on Sunday night when, after making an amazing defensive play to seal the Seattle Seahawks’ trip to the Super Bowl, he ranted in a postgame interview about his opponent.

On Tuesday, we caught a glimpse of the first when Sherman showed up for a sit-down with CNN’s Rachel Nichols for a mea culpa — but not for long.

“I probably shouldn’t have attacked another person,” he told Nichols in an exclusive interview that will air in its entirety Friday night on CNN’s “Unguarded.”

“You know, I don’t mean to attack him. And that was immature and I probably shouldn’t have done that. I regret doing that.”

But then, Sherman turned the spotlight on to him, making himself the victim, defending his actions and saying that what he regretted most was the way the media covered his rant.

He also said he was shocked by some of the racists responses he received.

“It was really mind-boggling the way the world reacted,” Sherman said. “I can’t say the world, I don’t want to generalize people like that because there are a lot of great people who didn’t react that way. But for the people who did react that way and throw the racial slurs and things like that out there, it was really sad. Especially that close to Martin Luther King Day.”

“I learned we haven’t come as far as I thought we had,” Sherman added. “I thought society had moved past that.”

The best in the game?

Sherman, 25, has played in the NFL for three years after a standout career at Stanford. He was named an All-Pro the past two seasons at cornerback, a position where you often find yourself standing alone and defending against the fastest offensive players on the field.

It takes a certain mix of bravado and confidence to excel at cornerback. And in Sunday’s game, Sherman brought both.

Sherman, who was defending 49ers receiver Michael Crabtree near the end of the tight contest, batted a ball to a teammate. That move ensured the Seahawks a trip to the Super Bowl.

The crowd was beside itself. And so, it seemed, was Sherman.

“I’m the best cornerback in the game,” he screamed during the post-game sideline interview. “When you try me with a sorry receiver like (the 49ers Michael) Crabtree, that’s the result you are going to get. Don’t you ever talk about me.”

Fox sideline reporter Erin Andrews asked, “Who was talking about you?”

“Crabtree,” Sherman angrily responded. “Don’t you open your mouth about the best, or I’m going to shut it for you real quick.”

Viewers were shocked. They’re more used to hearing players offer up cliches about what it takes to win, and hand down half-hearted congratulations to their opponents for being worthy adversaries.

The bile flowed almost immediately — tweets calling him a gorilla, an ape or a thug from the ghetto.

“Richard Sherman deserves to get shot in the (expletive) head. Disrespectful (N-word),” said one, expressing a common refrain.

Emotion and regrets

In his CNN interview, Sherman said it takes certain characteristics to become a successful football player.

It takes intensity. It takes focus.

And, he said, it takes anger.

He said he was in that emotional state after the play Sunday.

“If you catch me in the moment on the field when I am still in that zone, when I’m still as competitive as I can be and I’m trying to be in the place where I have to be to do everything I can to be successful … and help my team win, then it’s not going to come out as articulate, as smart, as charismatic — because on the field I’m not all those things,” he said.

Sherman said the vitriolic response surprised him.

What he did was “within the lines of a football field” — trash-talking an opponent but not hurting anyone, he said.

The commenters, he said, were out of bounds.

“They had time to think about it,” he said. “They were sitting at a computer and they expressed themselves in a true way.”

“But these people are acting like I attacked them in some way, like I went after them,” he added. “I did my job effectively. And afterwards, they interviewed me and I had an interview. Regardless of how that interview goes, it doesn’t give you the right to say — the things they were saying. And that’s the part that’s sad.”

All the way to the bank

There’s no such thing as bad publicity, the saying goes. And to hear Sherman’s agent tell it, the controversy has been good for him.

Sherman’s Twitter follower count has exploded in recent days. And the agent says his phone is ringing off the hook.

“Corporate America knows who Richard Sherman is,” said Jamie Fritz, who manages Sherman’s marketing deals. “I talked to brand managers this week and they are fired up. They love it. They say this is real. This is true. We finally have a player who is willing to speak his mind.”

But such exposure can be a double-edged sword, says Marc Lamont Hill, an associate professor of English education at Columbia University.

“He deserves all the marketing money he gets,” Hill told CNN’s Don Lemon. “My concern though is when they use this image, will they see him as an extraordinary athlete who has a knack for talking trash or frame him as another angry, violent athlete?”

Fritz admits there are two Shermans: The one who stormed off the field, and the one he wants America to see.

“The amount of emotion, anybody who’s played a competitive sport in a championship level knows what it’s like to have those emotions running,” said Fritz. “Here’s a guy who’s never been arrested, never said a curse word in a post-game interview, and when you look at his body of work off the field and what he does for the community and charity, it’s two completely different people.”