Leading up to the Baseball Hall of Fame class announcement on Jan. 21, we’ll be examining the cases of notable candidates every Thursday. We’ve already covered Félix Hernández, CC Sabathia, Andruw Jones, Francisco Rodríguez and a trio of second basemen in Chase Utley, Dustin Pedroia and Ian Kinsler. Up next is outfielder Ichiro Suzuki, who’s in his first year on the ballot.

Ichiro Suzuki liked to say he enjoyed hitting leadoff because the batter’s box was still pristine at first pitch. The imagery, like the manicured nature of the dirt, is perfect. The 24-square foot chalked rectangle became a Zen Garden for his unique artistry.

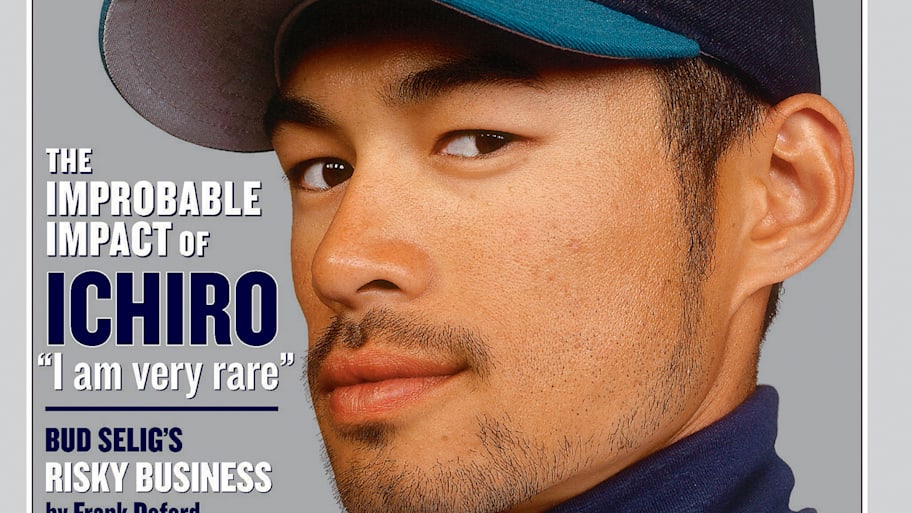

Ichiro will be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame Jan. 21 as a slashing, sprinting, irrepressible synonym of uniqueness. In the modern game of baseball, going back to when Babe Ruth popularized the home run, Ichiro is sui generis. Rod Carew had more power. Every Hall of Fame corner outfielder has a better OPS+. To find someone most like Ichiro, you must go all the way back to 1872, when Wee Willie Keeler was born. (Actually, even 5'4" Wee Willie outslugged him.) Ichiro was, in every sense of the phrase, a singular stylist.

Ichiro. Just Ichiro, the way it has been ever since 1994, when the new manager of the Orix Blue Wave, a non-conformist named Akira Ohgi, decided without consulting with his 20-year-old outfielder to put “Ichiro” on the back of the kid’s jersey rather than the traditional surname. As the name “Ichiro” embodies the legacy of “first-born son” and “Sukuzi” is the second most common Japanese surname, Ohgi found a way for someone with a common name to stand out.

Ohgi did more than create a novelty. He empowered a creative genius. Ohgi never hit much during a 14-year playing career. But he became a Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame manager with a gift for bringing out the best in his players. Ohgi, for instance, allowed pitcher Hideo Nomo to adhere to his own training regimen rather than institutional norms. Nomo flourished.

Likewise, Ohgi believed in allowing Ichiro to compete on his own terms. Ichiro was no sure thing at the time. He was not selected until the fourth round of the 1991 draft, when he weighed just 120 pounds at age 18. He hit .226 in part-time play over his first two seasons under Shozo Doi, his previous manager who was unconvinced Ichiro would ever hit with his slashing, gliding style.

Ohgi batted Ichiro leadoff and left him to his own ways. Ichiro was a natural righthander who became a lefthanded hitter on the instruction of his father, who knew the lefthanded batter’s box was closer to first base than the righthanded batter’s box. A fast runner, Ichiro could leverage that advantage even more by whipping his hips around early while keeping his hands back, creating a running start to this swing. In that debut season under Ohgi, Ichiro pounded out an astounding 210 hits in 130 games, batting .385. It was the start of 17 straight seasons in which Ichiro hit above .300. It was the start of a legend.

Not even the American obsession with power would move Ichiro off his natural artistry of simply making contact. In 2001, Ichiro became the first position player to jump from Nippon Pro Baseball to MLB when he signed as an international free agent with the Seattle Mariners. There was enormous pressure on him to succeed. His first few weeks of spring training were not impressive. True to form, Ichiro was slashing groundballs to the left side of the infield, many of them weakly hit. In one version of a famous tale that has many versions, Lou Piniella, his impatient Seattle manager, finally said to him, “You need to pull the ball.”

“No problem,” Ichiro said.

His next time up, Ichiro pulled a deep home run.

“Are you happy now?” Ichiro asked Piniella.

“You can do whatever you want for the rest of the year,” Piniella told him.

Ichiro went on to hit .350 with 242 hits, 127 runs (a career high) and 56 stolen bases (also a career high) and became the only first-year player to win the MVP and Rookie of the Year awards.

The uniqueness of Ichiro, listed at 5' 11" and 175 pounds, gained more resonance because of the comic size and shape of many of his contemporaries. He arrived during the greatest slugging era in baseball history, which was fueled by steroid use that went unchecked until a 2002 SI investigation that helped prompt the first testing for performance enhancing drugs. The 1999, 2000 and 2001 seasons included three of the six all-time highest slugging percentages, and the only time in baseball history the MLB slugging percentage was .427 or greater for three straight seasons.

It was during this run of unprecedented slugging, in 1999, that Nike captured the zeitgeist of the era with its “chicks dig the long ball” commercial. Ichiro, the counter-culture throwback, had his own answer, both in style and words.

“Chicks who dig home runs aren’t the ones who appeal to me,” Ichiro once said. “I think there’s sexiness in infield hits because they require technique. I’d rather impress the chicks with my technique than with my brute strength. Then, every now and then, just to show I can do that, too, I might flirt a little by hitting one out.”

Ichiro was a technician who made an art of hitting the ball softly. With Ichiro’s speed and running start style, any infielder that needed to move more than two steps to field one of his groundballs had almost no chance of throwing him out.

No hitter in the Hall of Fame is more associated with the humble single than Ichiro. Only five players had more singles than Ichiro: Pete Rose, Ty Cobb, Eddie Collins, Cap Anson and Derek Jeter. But none of them, or anybody who reached 3,000 hits, ever relied on singles more than Ichiro, who did so for 81.4% of his hits.

In 2004 Ichiro cranked out 225 singles, breaking a record by Keeler that had stood since 1898. It was one of two seasons in which Ichiro collected 200 singles. Combined, everybody else in baseball history did it once.

Per Baseball Reference, 22% of Ichiro’s hits never left the infield, including 64 infield hits in 2010. Speedy lefthanded hitters today such as Kyle Tucker and Corbin Carroll don’t have 64 infield hits in their careers.

He was so fast down the line that after Ichiro grounded into a double play in his first game of the 2009 season, he went the next 169 games, covering 781 plate appearances, before he did it again. Baseball Reference, using a metric that measures baserunning and staying out of double plays, rates Ichiro as the fifth best baserunner in MLB history, behind only Rickey Henderson, Willie Wilson, Johnny Damon and Tim Raines.

Ichiro reached 200 hits and 100 runs eight times, tying Keeler and Lou Gehrig for the most such seasons. He posted 10 straight 200-hit seasons, breaking the record of eight by Keeler.

On and on it goes. With Ichiro, finding statistical superlatives is like choosing a star out of the sky, or a hit among his record 4,367 as a professional. There are so many from which to pick. He is the single season record holder for hits (262), the only player to hit an inside-the-park home run in an All-Star Game, the greatest lefthanded hitter against lefthanded pitching at least since 1969 (.329 batting average, five points better than Tony Gwynn) and one of only four players with 3,000 hits, a .300 batting average and 500 stolen bases (Cobb, Collins, Honus Wagner and Paul Molitor are the others.)

This one nugget speaks to the relentlessness of his craft. Until Ichiro came along, the oldest player to get the first of 3,000 hits was Wade Boggs, who was 23. Ichiro did not get his first MLB hit until he was 27. He was 44 years old when he got his last, in 2018. Numbers 1 and 3,089 were a matched set of bookends to the greatness in between: ground ball singles up the middle that bounced several times.

Hall of Fame election results are announced Jan. 21. The only mystery with Ichiro’s first time on the ballot is whether he joins Mariano Rivera as the only unanimous electees in BBWAA voting history, which is a trivial matter to which too much attention is paid. (It’s mostly about the anomalous voters who didn’t vote for candidates such as Derek Jeter or Greg Maddux than it is about the value of the player, but that doesn’t stop the teeth gnashing about the “unanimous” narrative.)

There are 24 corner outfielders in the Hall, including recent committee electee Dave Parker (minimum: 75% of games in left field and/or right field). The current lowest OPS+ among them belongs to Lou Brock, at 109. Ichiro is at 107. He would have the second lowest slugging percentage among corner outfielders in the Hall, behind Harry Hooper, who was born in 1887. Ichiro was a corner outfielder who did not slug or walk much. Steve Finley has more total bases and more walks.

But that is pure math. For Ichiro to be a Hall of Famer without the traditional power from a corner outfielder only means he had to be extraordinarily great in other ways—and he certainly was in the field, where his spectacular range and arm won him 10 Gold Gloves. And yes, piling up single after single the way Ichiro did, like a mason building a massive wall of bricks, is also a math exercise. It is simple arithmetic. One plus one plus one plus one … until you get 2,514 bricks worth of singles, one more than the previous record by a corner outfielder—held by Keeler, his brother in light arms, who famously described his hitting theory thusly: “Keep your eye clear and hit ‘em where they ain’t.”

One veteran manager called him “the fastest man going to first I ever saw in my 30 years in baseball … No one who ever batted a baseball was more adept at placing a hit … He stood alone in this. His skill was uncanny. He seemed to sense what the opposing fielders would do, and he had the skill to cross them.”

A league executive said, “What struck me most … was that he was always a quiet, gentlemanly player in a period of the game when it was hardly the fashion to be quiet and gentlemanly. He never raised his voice in anger.”

Those observations were made of Keeler upon his death in 1923, by John McGraw and John Heydler, respectively. A hundred years later, Wee Willie Keeler’s name and exquisite batting style still resonate, like a timeless form of architecture or style of painting.

And the same words of praise from McGraw and Heydler for Keeler in 1923 could apply to Ichiro in 2025. That kind of permanence is not derived from mathematics. It swells from his most endearing and enduring quality. It is not all those hits. It is the art of Ichiro.

This article was originally published on www.si.com as Ichiro’s Singular Talent Gave Him All the Power He Needed.